How Alauddin Khalji Controlled Prices and Crushed Corruption

Economic Measures of Alauddin Khalji’s both agrarian and market-related policies must be viewed as strategic responses to internal state consolidation and external military threats, particularly the Mongol invasions. His overarching goal was to strengthen the central authority of the Delhi Sultanate while ensuring a well-equipped army through enhanced state revenues and economic control. The scale, systematic execution, and long-term impacts of his policies mark a significant phase in the development of the Sultanate.

Alauddin Khalji undertook a series of economic reforms that fundamentally transformed the revenue administration, market regulation, and price control systems of the Delhi Sultanate. His primary objective was to stabilize the economy, ensure state revenue for military campaigns, and suppress rebellions. These reforms had long-lasting effects on both urban and rural economic structures.

Table of Contents

AGRARIAN REFORMS of Alauddin Khalji

The Objective

Alauddin’s agrarian reforms were twofold:

- To bring a more direct relationship between the state and its rural economy, especially in the core region between Dipalpur and Lahore to Kara near Allahabad.

- To generate sufficient revenue for maintaining a large standing army, particularly in the wake of Mongol invasions.

Land Revenue and Khalisa

- Villages in this strategic belt were brought under khalisa i.e., lands under direct state control rather than assigned to nobles as iqta.

- Charitable grants (land gifted for religious or social purposes) were confiscated and turned into khalisa.

- Land revenue (kharaj) was fixed at 50% of the produce, assessed through measurement (paimaish).

- Fields were measured based on expected production per bisiwa (1/20 of a bigha), though exact methods remain unclear.

- Despite being assessed in kind, the revenue was collected in cash, prompting cultivators to sell their produce to banjaras (caravan traders) or in mandis (local markets).

Revenue Rates and Earlier Systems

- The actual increase in revenue burden is difficult to ascertain due to limited data on pre-existing tax norms under Rajput or early Turkish rulers.

- Dharmashastras proposed tax rates from one-fourth to one-sixth, increasing to half during emergencies. These were in addition to many sanctioned cesses.

- The bhaga, bhog, kar formula used for iqta assignment denoted this layered tax system.

- Measurement of land wasn’t entirely new; possibly revived by rulers like Balban, but Alauddin institutionalized it across a wide area.

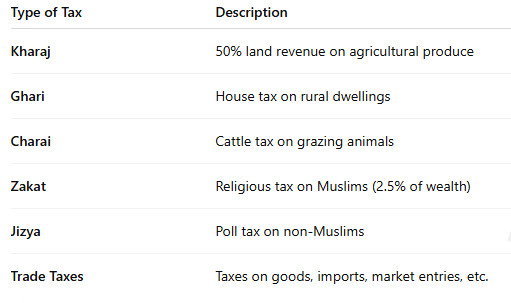

Taxation During Alauddin Khalji

🛡️ Alauddin Khalji’s Khums Policy and Controversy

Alauddin Khalji adopted a radically pragmatic and authoritarian policy that often went against orthodox Islamic law (Sharia). One of the areas where this is most evident is the Khums controversy.

🔍 What is Khums in Islamic Tradition?

Under Islamic law, Khums (literally “one-fifth”) refers to the portion of booty acquired during warfare or certain categories of wealth (like buried treasure, minerals, or profits) that must be set aside for Allah and the Prophet, to be distributed among:

- The descendants of the Prophet (Ahl al-Bayt),

- The orphans, needy, and travelers, and

- The Islamic ruler or state, for public welfare and defense.

In the ideal Islamic polity, the ruler was expected to implement this law, which was seen as a divine obligation.

🔹 1. Alauddin’s Rejection of Khums

- According to chronicler Ziyauddin Barani, Alauddin did not pay Khums as per Islamic law.

- He openly declared that he was not a Ghazi (fighter for Islam) and did not rule in the name of Islam. His governance, he claimed, was based on “political expediency” (Zarurat-e-Siyasat) rather than religious obligation.

- Alauddin retained the entire war booty (ghanimah) for the state and the royal treasury, using it to fund his army, reforms, and administration, rather than distributing one-fifth of it as Khums.

🔹 2. Ulema’s Objection

- The Ulema (Islamic scholars) criticized this decision. They considered his refusal to pay Khums a violation of Sharia.

- Alauddin, however, disregarded their protests, often marginalizing their role in political matters. He reportedly told them: “I do not know what is lawful or unlawful; whatever I think is politically expedient, I do.”

- This is a key example of how Alauddin separated religious law from state policy, prioritizing centralized control and secular governance.

🔹 3. Larger Religious Context

- His economic reforms, market control, and revenue policies often conflicted with Islamic injunctions.

- Yet, Alauddin did not reject Islam, but rather subordinated religious authority to statecraft.

- He allowed religious scholars to perform ritual duties, but excluded them from state decision-making.

📚 Historians’ Perspectives

- Barani admired Alauddin’s strength but was disturbed by his disregard for Sharia. He hoped future rulers would follow Sharia more closely.

- Irfan Habib considers Alauddin’s reforms, including the rejection of Khums, as early experiments in state-controlled economy and secular governance.

- Satish Chandra argues that Alauddin prioritized imperial interests over religious obligations, marking a departure from traditional Islamic polity.

- Peter Hardy

In “Historians of Medieval India”, Peter Hardy sees Alauddin as an early example of a Muslim ruler who subordinated Islamic theology to political authority:

“The refusal to pay Khums signified a breach not only with the ulema but also with the idea of a Sharia-bound monarchy.”

Hardy argues that this created a new model of kingship, one where political effectiveness trumped religious legitimacy.

⚖️ Significance of the Khums Controversy

- Separation of Religion and State: Alauddin established a quasi-secular state where politics dictated policy, not religion.

- State Supremacy: By denying Khums, he asserted state control over war booty and resources.

- Challenge to Ulema: He curbed the power of the religious elite, reshaping the balance between Islamic tradition and political authority.

- Foundation for Later Sultans: His bold policies influenced successors, many of whom maintained strong central control irrespective of religious mandates.

Role of Intermediaries

- Village-level intermediaries such as rais, ranas, rawats (chiefs), and muqaddams/chaudharis (village heads) had long collected revenue on behalf of the state.

- With the Sultanate’s consolidation, older chiefs lost influence, and new middle-level intermediaries emerged, called khuts and, later, zamindars (term first used by Amir Khusrau).

- However, not all territories of these chiefs were integrated into khalisa; many survived into later centuries, paying a lump-sum to the state.

Curbing Rural Aristocracy

- Alauddin sought to weaken the rural elite muqaddams, chaudharis, and khuts who enjoyed considerable privileges and wealth.

- Barani describes them as owning the best lands, indulging in luxury, riding expensive horses, and hosting lavish feasts.

- In a system of group assessment, they shifted their revenue burden onto weaker peasants.

- Alauddin reversed this: they were now made to pay charai (cattle tax) and ghari (house tax), like common peasants, and were deprived of the khuti (collection fee).

- Barani exaggerates that they were reduced to the status of balahars (menials), unable to ride horses or chew pan, and their women worked in Muslim households.

Limitations of Redistribution

- Despite reforms, real land redistribution did not occur. The aristocracy retained their best lands and some social status.

- However, out of fear of severe penalties, they became obedient and submissive, complying even with petty officials.

Impact on Peasants

- Although the curbing of aristocratic exactions was beneficial, peasants suffered under heavy taxation.

- Market reforms left them with barely enough for survival only enough for milk and buttermilk, according to Barani.

- Extreme hardship led some to sell their cattle and even wives to meet tax demands.

Revenue Administration

To manage the expanded khalisa and its demands:

- A detailed bureaucracy of amils (collectors), mutsarrifs (accountants), and gumashtas (agents) was deployed.

- The auditing system was tightened under Naib Wazir Sharaf Qais, making use of village patwaris’ bahis (ledger books) a system mentioned for the first time.

- Even minor discrepancies, like a missing jital, invited severe punishments, including imprisonment and torture.

- Officials received fair salaries, but bribery was met with harsh penalties.

- Barani vividly describes how these positions became socially undesirable comparable to chronic illness and no one wanted to marry their daughters to such officials.

Legacy and Influence

- Though Alauddin’s revenue measures were partly rolled back under Mubarak Shah, their legacy influenced future rulers:

- Sher Shah Suri and Akbar emulated his system of measurement and auditing.

- His attempts at rural restructuring and market integration had a lasting effect, increasing the town-village economic linkages.

Military Motivation and Economic Reforms

Following Mongol invasions, Alauddin built the fort city of Siri and strengthened military fortifications. Barani, in Tarikh-i-Firuz Shahi, emphasized that economic reforms were largely military-driven. The salary of a one-horse cavalryman was 234 tankas annually, with 78 tankas added for a second horse. Sustaining this military expenditure necessitated stable prices.

Alauddin regulated prices to prevent inflation. Though initially driven by military needs, he continued these reforms even when immediate threats subsided. He believed that controlling prices was essential for national prosperity. Barani claimed that profit-hungry Hindu merchants often exploited trade, siphoning wealth from Muslims a concern that partly motivated Alauddin’s reforms.

Observations of Amir Khusrau

In Khazain-ul-Futuh (1311), Khusrau praised the Sultan’s administration. He noted that peasants were relieved of excessive kharaj, and artisans benefited from reduced taxation. Artisans’ goods, earlier overpriced, now sold at regulated rates under the supervision of honest officials. Market weights were standardized using inscribed iron weights, replacing the unreliable stone measures. Strict penalties ensured compliance.

Khusrau described the Sultan’s vigilance lawlessness had vanished across the empire. Low grain prices benefitted both urban and rural populations. During droughts, grain was distributed from royal stores. The Dar-ul-Adal, Alauddin’s public palace-market, sold both indigenous and imported luxury items at controlled rates. Goods included rare textiles, fruits, and medicines from Persia and Central Asia.

Confirmation by Contemporary Sources

Barani corroborated Khusrau’s account 45 years later, affirming that reforms aligned with administrative resolutions. Although most medieval chroniclers overlooked the economic rationale behind these measures, Barani later delved into cost calculations. Even minor goods like needles and sandals were assessed. Determining grain prices was especially difficult, as it had to account for production costs, merchant profits, and artisans’ wages.

Alauddin did not enforce price controls through force. Instead, he controlled key merchants by financing their operations, gradually bringing trade under state regulation. His efforts inadvertently created a natural market, benefitting even later Sultans who did not actively manage the economy.

Impact on Hindu Merchants and Coinage

Alauddin marginalized Hindu Sahus, moneylenders, and big traders particularly Nayaks (grain) and Multani (cloth) merchants. Although their monopolies were curtailed, profits remained largely intact under the new price regime.

According to Ferishta, Alauddin issued tankas in both gold and silver. The silver tanka, valued at 50 jitals, remained in circulation for 250 years due to its stable silver content. A jital was a copper coin weighing slightly under 2 tolas. A seer weighed 24 tolas, and 40 seers made 1 maund the standard grain measure.

MARKET REFORMS

While agrarian reforms laid the fiscal foundation, market reforms ensured the effective functioning of the army and administration through price control and commodity regulation.

Administrative and Military Motives

- After the Mongol siege of Delhi, Alauddin needed a large standing army.

- Without price control, paying soldiers reasonable wages would bankrupt the treasury.

- Controlling prices meant soldiers could survive on modest pay a cavalryman with one horse could live on 238 tankas annually, and 75 tankas more for two horses.

Economic Suppression of Hindus

- Barani adds another reason: Alauddin aimed to economically weaken Hindus to discourage rebellion.

- This narrative reflects contemporary Islamic ideological biases, though it should be treated critically.

Market and Price Reforms

Alauddin restructured Delhi’s markets into four categories:

- Mandi (Grain Store): Central store from where grains were sold at fixed prices to various city wards.

- Sar-i-Adal: Market for sugar, spices, dry fruits, butter, cloth, and lamp oil.

- Animal and Slave Market: Continued into the 18th century, involving registration of all sales.

- Miscellaneous Goods Market: For other commodities.

Grain prices were tightly regulated. Wheat sold at 7 jitals per maund, barley at 4, and rice and lentils at 5. One silver tanka could purchase 88 seers of wheat or 98 seers of rice in Delhi an impressive purchasing power even by 1950s standards.

Control Over Grain Prices

Khusrau and Barani, contemporary chroniclers, emphasized the stability of grain prices during Alauddin’s rule, asserting that no price rise was permitted throughout his reign. The state fixed prices for various grains: wheat at 7 jitals per maund, barley at 4 jitals, and rice and lentils at 5 jitals per maund. Remarkably, these prices remained unchanged for the duration of his rule, a fact regarded as a marvel by observers of the time.

To put this in economic perspective, by mid-20th-century standards (around 1950), a single silver tanka issued during Alauddin’s reign could purchase 88 seers of wheat or 98 seers of rice in Delhi. This purchasing power reflects the strict regulation and relative affordability of grain under his system.

Grain Market Regulations

Alauddin implemented a series of six detailed regulations to control the grain market and ensure effective distribution and pricing:

- Appointment of Grain Controllers: Ulugh Khan was appointed as the chief controller of the grain market, aided by several assistants and an assistant controller. A dedicated news writer was also appointed to send daily reports about the grain market to the Sultan.

- Grain Collection from the Doab: Revenue from the fertile Doab region was collected in kind (grain) and brought directly to Delhi’s central granaries. Each ward had three houses designated as government grain stores, which were stocked thoroughly.

- Control Over Transporters: Malik Qabul was tasked with supervising grain transportation. The heads of the transporters were brought to Delhi in chains and forced to agree to strict clauses. They were made to live with their families on the Yamuna’s banks and kept under constant supervision. This created an efficient and regulated system of grain transportation, ensuring surplus supplies to Delhi.

- Prevention of Price Manipulation: Any form of buying grain at a lower price and selling it at a higher price than the government’s fixed rate was strictly prohibited. Officials of the Doab had to give written bonds to ensure compliance. Violators faced confiscation of goods and other penalties.

- Forced Selling by Peasants: To prevent hoarding by peasants, they were compelled to sell their grain immediately after harvest, directly to the government-approved transporters in exchange for cash. They were not permitted to store the grain at home. This ensured a continuous flow of cheap grain into the markets. However, peasants could sell their produce in government markets at fixed prices to earn a fair profit.

- Three-Tier Surveillance System: The Sultan received daily reports from three separate sources – the mandi controller, a news writer, and a network of spies. Alauddin, being literate and attentive, read every report himself. This surveillance ensured swift corrective action. For instance, when the mandi controller allowed a half-jital increase in price without authorization, he was physically punished.

Famine Control and Food Distribution

Alauddin’s proactive economic policy proved highly effective in times of distress. During droughts or poor harvests, Delhi did not experience famine or a surge in prices, thanks to the Sultan’s tight control over the grain supply.

To manage scarcity:

- Each ward received grain from central granaries according to its population.

- Individuals could purchase half a maund of grain.

- The central market ensured grain availability for nobles, their households, and attendants who lacked land ownership, proportionate to their numbers.

- Strict accountability meant that any mismanagement in the distribution system was met with punishment for the responsible official.

Control Over Luxury and Industrial Goods – Sar-i Adal

Alauddin also regulated luxury goods and imported industrial items via the Sar-i Adal, a centralized state-controlled market. Goods included:

- Sugar, cloth, dry fruits, clarified butter, lamp oil, and medicinal roots (especially for Unani medicine), often imported from Persia and Central Asia.

These were non-perishable items, allowing long-term storage and planned distribution.

Three main regulations governed this market:

- Establishment and Control of the Sar-i Adal: All goods whether imported by merchants or provided by the state had to be sold exclusively at the Sar-i Adal. Unauthorized sales elsewhere led to confiscation of goods and punishment of the seller. The market operated from morning till early afternoon.

- Fixing of Prices: Barani detailed the prices of many commodities. For example:

- Silk fabrics ranged between 3 to 16 tankas.

- A single tanka could purchase 20 yards of fine cotton cloth or 40 yards of regular cloth.

- A seer of sugar cubes cost 2½ jitals; 1½ seer of ghee cost 1 jital, and 5 seers of salt also cost 1 jital.

- Ordinary bed-sheet-sized cotton cloth cost between 6 and 36 jitals.

- Registration and Regulation of Merchants: Every merchant, regardless of caste or religion, had to register with the central commercial department. Their trade was tightly controlled. Those who brought goods from outside had to sell them in Delhi’s Sar-i Adal at government-fixed prices. This led to overstocking, as merchants began bringing in large quantities of goods, ensuring market abundance.

Consequences

Alauddin Khalji’s economic measures were highly effective and long-lasting. Even during the Mughal period, centuries later, the historian Ferishta noted that in some regions, grain prices fixed during Alauddin’s reign remained stable for decades. This indicates both the depth and sustainability of his price control mechanisms.

His ability to:

- Prevent inflation,

- Ensure availability of essential goods,

- Manage famines,

- Discourage hoarding,

- And regulate both wholesale and retail markets,

made his reforms one of the most remarkable economic experiments in Indian history.

No other Sultan before or after him could replicate such comprehensive control over prices and supply chains. Alauddin’s reforms show a clear understanding of statecraft, economic planning, and administrative rigor, all contributing to the financial strength and political stability of his empire.

Standard Secondary Sources used in this blog post

- Comprehensive History Of Medieval History Volume 5 Of Habib And Nizami

- Satish Chandra – Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals (Vol. I)

- Peter Jackson – The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History

- J.L. Mehta – Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India (Vol. II)

- THE SULTANATE OF DELHI (1206-1526)Polity, Economy, Society and Culture – ANIRUDDHA RAY

For More Such Blogs visit: https://historywithahmad.com/

Thanks for another informative blog. Where else could I get that kind of info written in such an ideal way? I have a project that I’m just now working on, and I’ve been on the look out for such info.

obviously like your web-site but you have to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very bothersome to tell the truth nevertheless I抣l certainly come back again.