The Mughal Nobility Under Aurangzeb

Explore the dynamics of the Mughal nobility under Emperor Aurangzeb, examining its structure, recruitment patterns, factional struggles, and the impact of these factors on the empire’s stability and decline. Aurangzeb Alamgir’s reign (1658–1707) marked a turning point in Mughal imperial history. His prolonged rule not only tested the resilience of the empire but also exposed underlying structural fissures within the Mughal polity.

A unique feature of the Mughal Empire was the international character of its ruling class. Chandra Bhan Brahman, a courtier during Shah Jahan’s reign, noted in his Chahar Chaman (Guldasta) that the Mughal nobility was composed of a wide array of racial and regional groups—Iranis, Turanis, Tajiks, Turks, Arabs, Abyssinians, Afghans, Shaikhzadas, Rajputs, Armenians, etc. This inclusivity transcended religious, racial, and geographical boundaries.

Historical Background and Evolution Of Mughal Nobility

- Babur’s Nobility: Dominated by Turanis (Central Asians), particularly begs and bahadurs. However, their tribal affiliations and independence posed challenges to Humayun, contributing to political instability.

- Akbar’s Nobility: Initially Turani-dominated with some Iranis. Recognizing the dangers of over-reliance on foreign elements, Akbar strategically recruited Rajputs (from 1562, before his policy of religious tolerance) and Shaikhzadas (Syeds of Baraha, Amroha, Delhi, Hisar Firuza) to balance the aristocracy. He remained hostile to Afghans, due to their earlier opposition to his father.

- Jahangir: Continued promotion of Shaikhzadas, especially the Baraha Syeds, and introduced Bundelas and Hill Rajputs. This led to accusations of bias against Turanis and mainstream Rajputs, such as the Kachhwahas and Sisodias.

- Shah Jahan: Reacted to Irani predominance by promoting Turanis, asserting his own Turani heritage. However, Iranis retained influence due to their competence in administration and finance. Cultural perceptions also favored the refined Iranis over the coarser Turanis.

Aurangzeb’s Nobility: Composition and Changes

Decline of Turanis

- Decline of the Uzbek Khanate led to fewer trained bureaucrats from Central Asia.

- Aurangzeb, unlike Shah Jahan, was disinterested in the North-West frontier and had reconciled with the loss of Qandahar, making Turani services less essential.

Continuity of Irani Influence

- Though Safavid Iran was in decline, Iranis continued to enter Mughal service from Bijapur and Golconda.

- Iranis remained important due to their administrative skills, especially in the Deccan.

New Recruits: Marathas and Deccani Afghans

- Aurangzeb’s Deccan-centric policy (spending 27 years there) led to large-scale recruitment of Marathas and Deccani Afghans, replacing Turanis and Rajputs.

- This caused resentment among the older nobility, who viewed the Empire as their preserve.

🔍 Note: The inclusion of Marathas and Afghans was an administrative necessity, not a sign of Aurangzeb’s religious tolerance. Unlike Rajputs, Marathas were not clan-based and less likely to integrate into the imperial service framework.

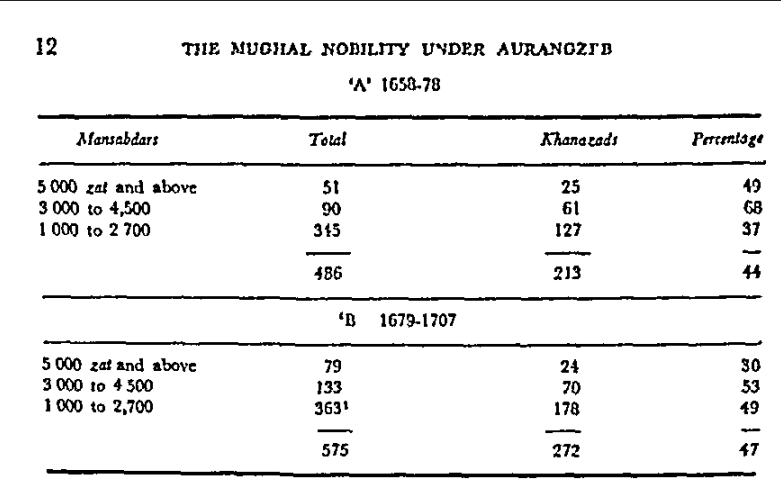

Statistical Insight

- Under Aurangzeb, non-Muslims made up 31% of the nobility.

- Under Akbar, they comprised 22%—challenging the perception of Aurangzeb as a strict religious bigot.

Factional Struggles in Aurangzeb’s Later Reign

Unity in Diversity—Breaking Down

Despite its internationalism, Mughal aristocracy functioned on the shared principle of loyalty to the Emperor. However, this began to unravel during Aurangzeb’s later years.

Causes of Factionalism

A) Economic Discontent & Mansab Allocation

- Each group had a conventional share in the usufruct (i.e., revenue, jagirs, mansabs).

- When this balance was disturbed, the disadvantaged factions rebelled (e.g., Turanis losing out to Marathas/Afghans).

B) Jagirdari Crisis and Cultural Identity

- Loss of confidence in the economic stability of the Empire encouraged nobles to form groups based on cultural identity to safeguard their interests.

- These groups began acting in self-interest, ignoring the broader imperial goals—contributing to political disintegration.

Precedents of Group Politics

- Even during the succession crisis post-Akbar, factions had formed (e.g., Turanis and some Rajputs with Khusrau, Shaikhzadas with Salim).

- In 1658, similar cultural alignments played roles in the war of succession.

- However, by Aurangzeb’s end, economic motivations and insecurity drove factional politics more than cultural affinity.

Conclusion

Aurangzeb inherited an internationally diverse but inherently fragile nobility. His pragmatic recruitment of Marathas and Deccani Afghans was an administrative imperative to consolidate the Deccan. However, the increased factionalism, driven by economic crisis, cultural pride, and declining imperial authority, contributed to the eventual fragmentation of the Mughal polity. The nobility’s failure to uphold collective imperial loyalty ultimately destabilized the Empire from within.

Sources: M. Athar Ali’s The Mughal Nobility under Aurangzeb,

Audrey Truschke’s Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India’s Most Controversial King,

Blog Of Professor Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi Centre Of Advanced Studies And Department Of History

Mughal Nobility and Aurangzeb

Read More:

One thought on “The Mughal Nobility Under Aurangzeb”